Professors: Request an Exam Copy

Print copies available for US orders only. For orders outside the US, see our international distributors.

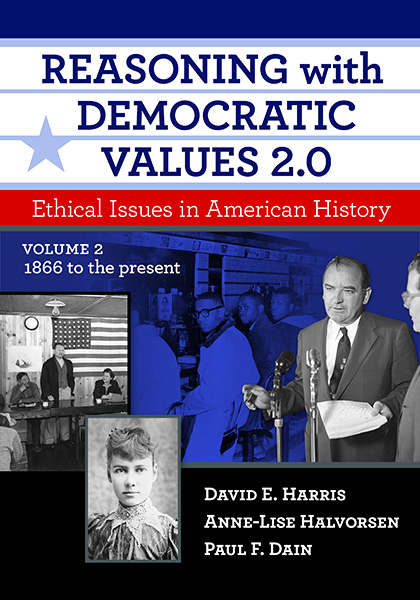

Second Edition

David E. Harris, Anne-Lise Halvorsen, Paul F. Dain

Publication Date: June 22, 2018

Pages: 256

“Will undoubtedly earn a place in many American history classrooms." —The Journal of Social Studies Research

"Clearly and imaginatively written… Students will find a refreshing departure from the staid historical writing that sometimes plagues other history texts." —Theory & Research in Social Education

Now thoroughly updated and extensively revised for use in today’s history classrooms, this time-honored classic has never been more important than right now. The new edition, Reasoning with Democratic Values 2.0, presents an engaging approach to teaching U.S. history that promotes critical thinking and social responsibility. In Volume 2 students investigate 19 significant historical episodes, beginning with the era of expansion and reform and ending with problems facing Americans in the contemporary era. Each carefully researched story examines an ethical decision made by an individual or group from the American past, and is guaranteed to excite students’ imaginations and spark lively classroom discussions involving core values of American democracy—liberty, equality, life, property, truth, and diversity. The discussions aim to develop more mature moral reasoning by students while deepening their knowledge of American history. Each chapter contains five types of learning activities: Facts of the Case, Historical Understanding, Expressing Your Reasoning, Key Concepts from History, and Historical Inquiry.

In Volume 2, students can grapple with such ethical dilemmas as:

You can also purchase a comprehensive Instructor’s Manual that includes the rationale for the teaching approach, guidance for selecting chapters, direction for leading classroom discussions of ethical issues, suggestions for assessment and grading, answers for the learning activities, and more!

PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT: The authors are available, at no fee, to conduct professional development programs for teachers and/or administrators regarding teaching with RDV 2.0. Visit www.rdv2.org for more details, including author contact information. The authors have committed their royalties to teacher education.

ALSO AVAILABLE—

Reasoning with Democratic Values 2.0, Volume 1: Ethical Issues in American History, 1607–1865 by David E. Harris, Anne-Lise Halvorsen, and Paul F. Dain

Reasoning with Democratic Values 2.0 Instructor's Manual: Ethical Issues in American History by David E. Harris, Anne-Lise Halvorsen, and Paul F. Dain

David E. Harris is a retired professor of teacher education at the University of Michigan. Anne-Lise Halvorsen is an associate professor in the Department of Teacher Education at Michigan State University, College of Education. Paul F. Dain is a retired government teacher and social studies department chair at Andover High School in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan.

"Reflection upon the sources of our ethical views is imperative in our present moment. At a time marked by polarization and incommensurate moral disagreement, citizens must practice a rather heroic form of civility and sober examination of opposing views. Reasoning with Democratic Values 2.0 provides both the raw material and appropriate structure for students to develop these habits, and it will undoubtedly earn a place in many American history classrooms."

—The Journal of Social Studies Research (for second edition)

"These volumes are engaging, clearly and imaginatively written, and frequently invite sophisticated thinking about difficult ethical issues within U.S. History. Through the well-selected stories, students will indeed recognize that history is replete with ethical issues that intricately intertwine with democratic values. Students will also find a refreshing departure in these books from the staid historical writing that sometimes plagues other history texts. Through well-designed readings and learning activities, these new editions accomplish what the authors’ intended—to promote social responsibility through informed and ethical use of democratic values."

—Theory & Research in Social Education (for second edition)

“Among the best supplementary materials for U.S. history known to this reviewer. The cases are provocative; they stimulate student interest, they promote a depth of historical understanding often absent from history instructional materials, and they promote important student skills. The curriculum is a fine blend of historical content and thoughtful pedagogy, systematically structured to promote social responsibility among students—one of the enduring instructional goals of social studies education.”

—Social Education (for first edition)

“Reflective, engaging, and timely, volume II of Reasoning with Democratic Values 2.0: Ethical Issues in American History positions readers to move beyond being a passive consumer of history and take up a sophisticated examination of ethical dilemmas within American history.”

—Teachers College Record

“Reasoning with Democratic Values 2.0 is a powerful approach to learning history that is highly engaging for young people. The lively writing of exciting and true stories provide ample background to engage students in discussions of well-framed questions that are perennial and important.”

—Diana Hess, dean, University of Wisconsin Madison’s School of Education

"I cannot imagine a more valuable or timely resource for teachers of U.S. history. Ethical reasoning is joined with historical reasoning—values with inquiry—in an array of well selected cases. This curriculum belongs in every U.S. history classroom."

—Walter C. Parker, professor of social studies education, University of Washington

“How can American citizens learn to converse across their differences? Part of the answer surely lies in history instruction, which can teach us about divisions that have wracked the nation and--most of all--about how we have bridged them. These superb books will help do exactly that. Clearly organized and eminently balanced, these volumes are suffused with the same democratic spirit they aim to promote.”

—Jonathan Zimmerman, University of Pennsylvania

“These volumes will help build a deeper understanding of significant historical concepts and present wonderful opportunities to engage in critical thinking around complex ethical issues.”

—Amy B. Bloom, J.D., social studies education consultant, Oakland Schools

"Reasoning with Democratic Values 2.0 enriches learning in social studies classrooms. The chapters not only provide thorough historical accounts, the narratives enhance teachers' and students' understanding of the complexities of decisionmaking in an imperfect democracy. These books are a useful resource not only in U.S. history classrooms, but also for government, sociology, ethnic studies, and ethics classes."

—LaGarrett King, University of Missouri

"Reasoning with Democratic Values 2.0 serves as an important contribution to help students think—and act—as ethical, prosocial members of a democratic society, which is certainly needed in this age of reactive and polarizing political discourse and action. I'm fully behind educators' efforts to inject discussions about ethical issues in the classroom as a way to help students better understand who and what is affected by their decision-making."

—Paul Barnwell, education consultant and former Kentucky public school teacher

Tentative Table of Contents

Dear Readers

PART VI: RECONSTRUCTION AND THE GILDED AGE (1866-1890)

Chapter 21. Pioneering Suffragists: Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Universal Suffrage

Chapter 22. The Last Battle of the Civil War: The Presidential Election of 1876

Chapter 23. Kill the Indian and Save the Man: Luther Standing Bear and the Carlisle Indian Industrial School

Chapter 24. Telling a Lie to Discover the Truth: Nelly Bly's Investigative Journalism

PART VII: INDUSTRIALIZATION AND REFORM (1891-1918)

Chapter 25. Richest Man in the World: John D. Rockefeller and the Standard Oil Company

Chapter 26. The Wobbly Giant: Conflict Between Labor and Capital on the Frontier

Chapter 27. General Manager of the Nation: Nelson W. Aldrich and the Income Tax

Chapter 28. A War to End All Wars: American Entry into World War I

PART VIII: BETWEEN THE WARS (1919-1940)

Chapter 29. Stealing North: Escaping Jim Crow

Chapter 30. Dust Can’t Kill Me: Bank Foreclosures in the Great Depression

Chapter 31. Deportees: Deportation and Repatriation to Mexico: 1929-1939

Chapter 32. United We Sit: The Flint Sit-Down Strike

PART IX: HOT AND COLD WAR (1941-1989)

Chapter 33. Yearning to Breathe Free: The Voyage of the St. Louis

Chapter 34. Tell Them We Love Them: Japanese Americans During World War II

Chapter 35. Naming of Names: Elia Kazan and McCarthyism

Chapter 36. Crime After Crime: The Burglary of an FBI Office

PART X: CONTEMPORARY AMERICA (1990-2017)

Chapter 37. 40 Acres and a Mule: Reparations for African Americans

Chapter 38. Bake Me a Cake: Wedding Cakes and the Constitution

Chapter 39. Accord Discord: The Paris Climate Accord of 2015

About the Authors

Crime After Crime

Burglary of the FBI

In late 1970, when protests against the Vietnam War were raging across the country, William Davidon, a mild-mannered professor of physics at Haverford College in Pennsylvania posed this startling question to a small group of people: "What do you think of burglarizing an FBI office?"

Those asked were stunned. What, they wondered, could be gained by breaking into an FBI office? The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), headed for nearly half a century by legendary Director J. Edgar Hoover, was revered as the agency that protected Americans from crime. Further, they thought, security of FBI offices would be so tight that any one who dared to attempt to break in to one of them would surely be caught and sent to prison.

Professor Davidon had come reluctantly to the idea of such a burglary. He believed that the FBI was spying on Americans and violating their constitutional right to dissent. The agency that was supposed to fight crime, Davidon suspected, was committing crimes. Breaking into an FBI office would be a crime to expose what he considered a crime against democracy.

Davidon approached nine people with his burglary suggestion. Only one of them turned him down. The other eight trusted him, and although shocked, listened to his explanation. They knew that he was thoughtful and not reckless. He was someone they respected and whom they thought would engage in high-risk protest only if it promised to be effective.

The eight people approached by Davidon met as a group for the first time shortly before Christmas of 1970. Repugnant as a burglary was to them, they thought it might be the only way to expose evidence that the FBI was violating the right of Americans to dissent. As passionate opponents of the Vietnam War, all eight, and Davidon, suspected that the FBI was suppressing protest against the war.

The preceding year had been one of deep division, unrest, and violence across the country. In November 1969 the nation was horrified to learn that American soldiers had massacred 504 Vietnamese, including children, women, and elderly people in the small hamlet of My Lai. The commander of the soldiers accused of the massacre, Lieutenant William Calley, was convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment at hard labor. President Nixon reduced the sentence to 3 months and ordered that Calley serve his sentence under house arrest rather than in prison.

Many public officials lashed out at war protesters. One of the more extreme attacks on anti-war activists came in 1970 from Governor Ronald Reagan of California. He said "that if it takes a bloodbath to silence the demonstrators, let’s get it over with."

In March, three members of a violent protest group known as the Weather Underground were killed in an explosion they accidentally set off while making a bomb in a New York town house.

In a speech in April, President Nixon announced that the United States was invading Cambodia after months of secretly bombing it. The announcement set off more antiwar protests than ever before. Two days following the President's speech, James Rhodes, the governor of Ohio, declared martial law at Kent State University and ordered the Ohio National Guard to patrol the campus. The governor called protesting students "the worst kind of people we harbor in America." The next day four students were killed and nine injured by National Guard gunfire on the Kent State campus. It was the first time that Americans were killed while protesting the war.

Several days after the Kent State shootings, two unarmed students were killed by police on the campus of Jackson State University, an historically black college in Mississippi.

The following Friday, hundreds of construction workers in the financial district of New York City attacked scores of students gathered for a vigil to mourn the students killed at Kent State. The attackers used crowbars and other heavy tools wrapped in American flags to beat the students. From their office windows high above, financial district workers tossed ticker tape to celebrate the violence in the streets below them. Vice President Spiro Agnew wrote a letter to the union official who organized the attacks on the students congratulating him for "his impressive display of patriotism."

In the middle of the night of August 24, 1970, a bomb exploded in front of Sterling Hall on the campus of the University of Wisconsin at Madison. Sterling Hall housed the Army Mathematics Research Center. A 33-year-old physics researcher, the father of three young children, was killed by the blast, and four people were injured.

Davidon, distressed by the increase of violence in the country, believed that the Vietnam War was a major cause of it. He wanted to step up protest against the war. At the same time, his suspicion was growing that the government was unlawfully suppressing protest.

At first he was skeptical of rumors he heard from members of various peace groups that there were FBI spies in their midst. As the rumors persisted, Davidon came to believe that they were probably true, that peace organizations were being infiltrated by informers. He feared that FBI Director Hoover was using his power to spy on those who opposed the war. With freedom to dissent obstructed by the government, Davidon thought, free expression became meaningless. How, he wondered, could a government that claimed to be fighting a war for people's freedom in another country at the same time suppress dissent by its own people?

He was, however, not sure that the FBI was suppressing dissent against the war. So far there were only rumors and suspicions. He now focused his mind on how to prove or disprove the rumors. As he framed the problem, he came to the conclusion that he needed hard evidence. Assumptions would not do. To convince himself he would have to find evidence of official suppression of dissent. Government spies, informants, tapping of telephones, threats to anti-war activists, or other actual surveillance measures by government agents to intimidate protesters would have to be uncovered for Davidon to confirm his suspicions. If he could find evidence of such tactics and present it to the public, he was confident that people would demand that the suppression be stopped.

This perplexing problem led Davidon to consider burglary. He disliked it as a tool of resistance as he had when he had used it once before. In early 1970 he had reluctantly joined Catholic antiwar activists in raiding draft board offices to destroy records of young men eligible to be drafted into compulsory military service. It seemed to him, however, that there was no other way now to get documentary evidence of FBI operations except by breaking into an FBI office and stealing files.

John and Bonnie Raines were the first two trusted people approached by Bill Davidon. John had experience with resistance during the civil rights movement. Beginning in 1961 he went south nearly every summer to protest racial discrimination. As a Freedom Rider he had dangerously tested integration of interstate buses traveling between cities of the South. One night in a small southwestern Georgia town he had been arrested, and jailed. He was rescued by a local black farmer who, fearing for Raines's safety alone in a jail cell, put up his small farm as bail so that John could be released and leave town.

Tall, blond, and handsome, with striking blue eyes, John Raines, the son of a prominent Methodist pastor, and later bishop of Indianapolis, had been raised in an affluent, liberal area of Minneapolis. He referred to his upbringing as "firmly inside a world of privilege and power." Minneapolis mayor, future U.S. senator, and vice president of the United States, Hubert Humphrey, had been a neighbor who occasionally dropped by his family’s home.

Bonnie Raines, warm and engaging with long black hair and a radiant smile grew up in Grand Rapids, Michigan. She attended Michigan State University where she was a good student and a cheerleader. To earn money for college, she worked summers as a waitress at a stately resort in Glen Arbor, Michigan, where John's family had a vacation cottage overlooking beautiful Glen Lake.

One summer night in 1961 John went to the resort for dinner and sat at one of the tables Bonnie was serving. They were attracted to each other, fell in love, and married a year later in Grand Rapids. After their wedding, they moved to New York. By 1970 they had three children.

John became a professor of religion at Temple University in Philadelphia. Bonnie was the director of a daycare center and studying toward a graduate degree in child development at Temple. The evening they met with Davidon at his home, they were stunned by his question. As Davidon explained his thinking about a burglary to the Raineses that evening, John and Bonnie found themselves agreeing with him. They felt deeply about the constitutional right to protest and, if government officials were trying to silence protestors, they wanted them exposed.

Every evening for a week the Raineses discussed Davidon's question with each other after dinner as their three children, ages 7, 6, and 1, slept upstairs. With deep anguish they grappled with the conflict between their ideals and the well-being of their children. Were they willing to threaten the future of their family? Finally, though skeptical that an FBI office could be burglarized, they called Davidon to tell him that they would take the risk and join in his search to determine whether the rumors of infiltration by government spies were true. Before committing, they asked John's brother and sister-in-law whether they would raise the three Raines children if Bonnie and John went to prison. The children's aunt and uncle promised that they would.

With John and Bonnie on board, before the December holidays, Davidon recruited six more people for the burglary. All members of the group were passionate opponents of the Vietnam War. They confronted in 1970 a disturbing spiral of casualty numbers: in some months more than 500 American soldiers were killed. In the end more than 58,000 Americans, 1.1 million Vietnamese military, and 2 million Vietnamese civilians were killed in the war. They were also mindful of a growing chorus of opposition to the war, including hundreds of thousands of young men who refused the draft and a half-million troops who deserted by 1971. They were also inspired by the example of Martin Luther King's Letter from a Birmingham Jail, in which he called for nonviolent civil disobedience in protest of unjust laws.

The prospective burglars were fully aware of the danger in what they were plotting to do. They could lose their freedom and possibly their lives. In December 1970, pledging strict secrecy to one another, they began meeting in the third floor attic of the Raineses' home located in Germantown, a suburb of Philadelphia, to make their plans. They named their group the Citizens' Commission to Investigate the FBI. Their goal was to break into the FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania, a sleepy town 15 miles southwest of Philadelphia; take as many files as they could carry away; review the files and, if they contained information the group believed the public ought to know, distribute them to the public.

Their first task was to choose a night for the burglary. They chose March 8, 1971, because that date was the night of the highly anticipated world heavyweight championship-boxing match between Muhammed Ali and Joe Frazier. The burglars hoped that the nation would be riveted to the fight at Madison Square Garden the night they were breaking into the FBI office.

The nights of their planning meetings, the group would have dinner at the Raineses' house. After dinner a babysitter arrived. John, Bonnie, and the other plotters adjourned to the attic. Following their meeting, two to a car, the burglars would drive to Media to case the area near the FBI office. They would often sit for hours in their cars during bitter cold nights of January and February. Afterward, they would return to the attic to discuss what they had discovered.

While casing in Media, they carefully monitored many conditions, including: parking of vehicles near the FBI office; movements of residents in and out of the building as well people who worked in offices located on the first and second floors of the residential apartment building in which the FBI office was located; schedules and routes of local police who patrolled the neighborhood; lighting patterns in the FBI office and nearby offices; closing times of nearby restaurants and bars; the schedule and movement of the county courthouse guards across the street from the FBI office.

During one of the planning sessions in the attic it was suggested that a crow bar be used to break into the FBI office. One member of the group thought that would be too noisy. Instead, he said that he would learn to pick the lock. He then joined a locksmith association and researched locksmithing in the library of the association. He had walked by the FBI one day after Davidon invited him to join the group, and he observed that the lock on the door was a simple five-tumbler lock, easy to pick.

Thorough as the burglars were casing the area outside the FBI office, they needed also to inspect it carefully from inside. For that they turned to Bonnie Raines. The scheme was for her to masquerade as a college student.

Not many people visited FBI offices. Bonnie needed a way for her to visit without arousing the suspicion of agents. There were key questions that had to be answered: Were the cabinets and desks locked? Were the floors carpeted? Was there an alarm system or surveillance cameras in the office?

Bonnie was a very youthful looking 29 years old. Posing as a college student, she called the FBI office to ask for an appointment and requested of the agent in charge a half-hour interview. As a student in a local college, she said, she was doing research for a class assignment about hiring practices. The agent agreed to meet with her at 2 o'clock a few days later.

The burglars spent time preparing for Bonnie's bogus interview. They prepared questions for her to ask. They considered what her personal appearance would be, for example, how she should wear her long black hair. She often wore it in long pigtails. For her visit to the FBI office, it was decided that she would wear her hair pulled back in a barrette and tucked under a wool hat. She wanted to reduce the chances that she might later be recognized from photographs that the group assumed law enforcement officers might have taken at anti-war demonstrations Bonnie had attended. She decided to add a pair of horn-rimmed glasses to her disguise. To avoid leaving fingerprints, she would wear gloves. Following the advice of the group, Bonnie dressed for the interview as a nerdy coed, dressed in a skirt, sweater, and long winter coat.

The afternoon of her appointment, Bonnie arrived, as planned, 15 minutes early. She excused herself for arriving early by saying that the bus she took arrived earlier than expected. Actually, John had driven her and dropped her off out of sight from the FBI office. The early arrival was a ruse for her to sit and survey the office carefully while waiting for the agent to start the interview. While waiting, she asked one of the agents if she could see an employment application form. The purpose of her request was to observe whether the agent would have to unlock a file cabinet to get the form. She was relieved to see that the file cabinet was not locked.

From where she sat while waiting she saw two other rooms in the office. She noticed open blinds covering the windows. If the burglars were to use flashlights, she noted, they would have to do so carefully to avoid streaming light between the slats.

During the interview with the agent in charge, Bonnie thought he was a nice guy, the kind of person one might like to have as a neighbor. He didn’t seem to suspect anything unusual. Her gloved hands seem to arouse no suspicion while she took notes during the conversation.

The offices had wall-to-wall carpeting that would help muffle any noise made by burglars. The interview lasted an hour. While taking leave Bonnie asked where the restroom was located. An agent told her the restrooms were outside the office, gave her a key, and pointed down the hall. The burglars wanted to know whether there would be an open restroom where they could hide if necessary. Knowing now that a key was needed, Bonnie realized that there would be no place to hide the night of the burglary.

She tracked the paths of all electrical cords in the office and discovered that none led to an alarm system. She saw no surveillance cameras. She checked the lock on the office door and confirmed that it was a simple lock that could easily be picked. She also noticed that the second door that opened into the external hallway was blocked on the inside by a large file cabinet. The burglars would have to enter, as she had, through the main entrance.

After exiting the building, Bonnie walked to the prearranged spot where John was waiting with the car. She was visibly shaking as she opened the car door. Soon she calmed down. Ecstatically, she told John that she was now sure the burglary could be done. John was buoyed by her optimism, but he also felt deep foreboding. He especially feared what might happen to his children if the burglars were caught.

It was now time for the "Commission to Investigate the FBI" to act on their burglary plan. Two challenges were daunting. First, residents of the apartment building might come or go through the building entrance and open stairwell at any time. Second, across the street from the FBI office, a guard was stationed around the clock inside the glass door at the Delaware County courthouse. The burglars would be visible to the guard when they entered the FBI office building.

A few days before the burglary was to take place, one of the members of the group announced that he was quitting and left the meeting. He knew all the details of the plan. The remaining burglars were haunted by the possibility that he would reveal their plot.

At 6:30 p.m. on March 8, the Raineses greeted the babysitter and anguishly hugged their young children. It was time to go to meet their co-conspirators at the motel room they had rented as a staging site for the night of the burglary. They drove to the motel in their family station wagon and met their six accomplices at the motel at 7 o'clock.

The locksmith and the four members of the inside team—those who would enter the office and steal the files—wore "uptown" clothes so they would blend with residents of the neighborhood. The locksmith, Keith Forsyth, who would enter the office first, wore a long secondhand Brooks Brothers topcoat to conceal his burglary tools.

Forsyth and John Raines left the motel room in separate cars between 7:30 and 8:00 p.m. Forsyth drove to Media to break into the FBI office. John Raines drove to a parking lot at Swarthmore College where he would wait for the burglars to arrive with stolen files to be transferred to his family station wagon, now being used as a getaway car.

Forsyth parked a short distance from the FBI office. Wearing a suit and tie, he carried a briefcase containing his lock-picking tools. He entered the apartment building, headed upstairs to the second floor, and walked directly to the FBI office door. He expected to pick the lock in 30 seconds, but he was suddenly shocked to discover that he would be unable to pick it at all. There was now a second lock on the door, a high security lock on which his tools would be useless. Stymied, he walked to a phone booth and called the motel. Davidon told him to return to the motel.

The group was alarmed. Why, they wondered, was there a second lock on the door? Had it been overlooked before? Had Bonnie Raines’s interview visit prompted the FBI to add a second, more secure lock? Had the conspirator who dropped out betrayed them? Were there armed agents waiting inside the office for the burglars?

Bonnie was closely questioned about what she remembered about the second external FBI office door. It was barricaded on the inside by a tall metal cabinet. She thought it would be very difficult to enter through that door. Nonetheless, she saw it as their only chance to succeed, and the others agreed to go ahead.

Forsyth drove back to the FBI office and arrived at 10:40, just as the bell rang to start the Ali-Frazier fight, later than the burglars had expected. This time the locksmith carried a crowbar with him. He easily picked the simple lock on the second door. Next, using the crowbar, he popped out the deadbolt lock at the top of the door. He pushed on the heavy wooden door, but it would not move. He couldn’t apply enough force. He needed a heavier tool. He went to the trunk of his parked car and brought back the bar used with a jack stand. Back at the office door he was terrified. Residents could walk by at any moment as he lay on the floor trying to nudge the door open with the bar. If he knocked over the cabinet on the inside, it would make a loud noise, surely to be noticed by the building caretaker who lived in the apartment directly below the office.

Amidst his terror, Forsyth remembers taking a small measure of comfort while lying on the floor and prying the door open. He could hear sounds of Ali-Frazier fight crackling in the hallway from apartment residents listening on their radios. As the burglars had hoped it would, the fight was providing some cover for their break-in.

For several minutes, Forsyth slowly and cautiously pushed the door until it was open barely enough for him to squeeze inside. He then drove back to the motel where everybody was relieved to see him and delighted to learn that the door was unlocked. The FBI office was ready to be entered.

The inside crew of four burglars was driven to the Media office. Each of the four carried two large suitcases through the front door and into the building. They entered the office through the door that Forsyth had dislodged. In the dark, except for a cautiously used flashlight, they opened every cabinet and broke locks as necessary to open locked drawers.

When every drawer, shelf, and cabinet had been emptied, one of the burglars called the motel to give a cryptic signal that the inside crew was ready to be picked up. Their suitcases were bulging with all the files in the Media FBI office. They were picked up in two getaway cars and, switching cars as a precaution en route, set off to the remote farm house where the burglars had planned to sift and winnow the stolen files.

Searching through long days and nights with little sleep, the burglars discovered files that described surveillance and intimidation by the FBI, including eavesdropping, entrapment, and the use of informers. What they found confirmed suspicions that the nation’s leading law enforcement agency was engaged in illegal political spying.

FBI Director Hoover was infuriated when he learned of the Media burglary the next morning. He made it a top priority and set in motion one of the most extensive investigations in the history of the FBI. Nearly 200 agents were transferred to Philadelphia to work on the case.

Having completed what they set out to do, the burglars agreed never to meet with one another again. The following day John Raines drove to Princeton and dropped five packets of FBI documents in a mailbox, addressed respectively to U.S Senator George McGovern of South Dakota, U.S. Representative Parren Mitchell of Maryland, columnist Tom Wicker of the New York Times, investigative reporter Jack Nelson of the Los Angeles Times, and reporter Betty Medsger of the Washington Post.

Senator McGovern condemned the burglary refusing to be associated what he called an "illegal action by a private group." Congressman Mitchell turned the documents over to the Department of Justice while declaring both the burglary, and the FBI surveillance of student and peace groups it exposed, crimes to be dealt with.

The mailed documents revealed that the FBI had been monitoring student groups, especially those of black students. The bureau had paid informers who reported on the activities of students and professors. The stolen files also revealed that personal records of people not linked to any criminal activity, for example phone records and checking account records, had been procured by agents without subpoenas. There was also evidence that banks, credit card agencies, employers, landlords, law enforcement officers, and military recruiters provided confidential files to the FBI, without regard to privacy rights.

It was the Washington Post that first published the stolen files. The attorney general of the United States, John Mitchell, tried to deter the paper's publisher. He warned that public release of the files taken from the Media FBI office could endanger the lives of federal agents and the security of the United States.

This was the first time that a journalist had been given secret government documents by sources outside government who had stolen them. Possessing stolen documents was a federal crime. The attorney general threatened to deny broadcast licenses for stations owned by the Washington Post if the paper went ahead with publication of the Media burglary documents. Contrary to the advice of its attorneys, the publisher and editors of the Washington Post, acting boldly and asserting the constitutional right to a free press, decided to publish the documents.

Other newspapers across the country followed the lead of the Post. A storm of criticism of the FBI and Director Hoover followed. For example, the Philadelphia Inquirer, long an admirer of Hoover as an anti-communist watchdog and crime fighter, declared that the questions raised by the stolen documents "are questions too fundamental in a free society, with implications too suggestive of police state tactics, to be brushed lightly aside."

One of the stolen documents, a simple routing slip, contained the mysterious word COINTELPRO. Journalist Carl Stern of NBC, using the Freedom of Information Act, persisted against determined resistance by the FBI to uncover the meaning of the term.

He discovered that COINTELPRO was an acronym (Counter Intelligence Program) for a series of highly secret and sometimes illegal projects conducted by the FBI beginning in 1956. Americans who criticized the Vietnam War or were considered "subversive" were targeted for spying. They included U.S. senators, civil rights leaders, journalists, and athletes. Among them were Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Albert Einstein, and Eleanor Roosevelt. Groups deemed subversive were infiltrated by FBI informers.

COINTELPRO tactics included not only infiltration of groups but also planting false media stories, forging of correspondence, disrupting meetings, accusing activists of crimes they did not commit, opening mail, conducting wiretaps, giving perjured testimony and false evidence, and illegal break-ins.

These extreme methods constituted harassment, invasion of privacy, and violation of the right to dissent. Little or none of them pertained to people or organizations that planned or committed crimes. The spying and dirty tricks had little or no connection to the official mission of the FBI: law enforcement or intelligence gathering to safeguard Americans from crime.

These revelations, exposed by the stolen Media files, created a national uproar. For the first time, there were widespread calls from members of Congress and newspaper editorials for investigation and oversight of the FBI and its powerful director. In response, Congress authorized the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, known as the Church Committee for its chairman, Senator Frank Church, Democrat of Idaho. Following extensive investigations, the Church Committee concluded that the FBI had "violated specific laws and infringed constitutional rights of American citizens." It recommended legislation that was adopted to create permanent intelligence oversight committees in both houses of Congress. Also adopted under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) was a special court to control electronic surveillance by intelligence agencies.

Although there were close calls, none of the Media burglars was caught. FBI agents missed only by minutes discovering Bonnie Raines at her house one day. They had a sketch of her, drawn from memory of the day of her bogus interview at the FBI office in Media, but they were never able to identify her. During the years following the break-in, all of the burglars lived their normal lives, but they were haunted by fear that the next knock on their door would be FBI agents coming to arrest them.

The statute of limitations for burglary takes effect 5 years after the crime. By March of 1976 the burglars could no longer be prosecuted, yet they planned to keep their secret. It was revealed accidentally. The Washington Post reporter, Betty Medsger, to whom the stolen FBI files had been sent in 1971 had been an acquaintance of the Raineses when she worked as a reporter for the Evening Bulletin in Philadelphia. During a weekend visit to that city many years after the burglary, she had dinner at the Raineses' house. John Raines introduced Betty to the Raineses' teenage daughter, "Mary, this is Betty Medsger. We want you to know Betty, because many years ago, when your dad and mother had information about the FBI we wanted the American people to have, we gave it to Betty." Medsger was amazed to find out that her hosts and old acquaintances were among the Media burglars.

In 2014, during a question and answer session following a public presentation about the burglary, John Raines was asked what it was that had especially motivated him, unlike other civil rights and anti-war activists of the era, to move across such a hazardous line and become a burglar. After a long, reflective pause he said, "I have a background of belief in Jesus of Nazareth who took the fight for justice to the Cross."

The major sources for this chapter were:

Medsger, Betty. The Burglary: The Discovery of J. Edgar Hoover’s Secret FBI. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014.

Harris, David. Recorded interview of Bonnie and John Raines. Glen Arbor, Michigan: July 22, 2014.

LEARNING ACTIVITIES FOR “CRIME AFTER CRIME”

Facts of the Case

1. Why did William Davidon propose burglarizing an FBI office?

2. Why did Bonnie and John Raines agree to participate in the burglary?

3. What did the stolen Media files reveal about FBI operations?

4. Why did the Washington Post hesitate to publish the stolen secret FBI documents?

5. What changes in federal law were put in motion as a result of the Media burglary?

Historical Understanding

1. Describe the climate of violence in the United States during the year preceding the Media burglary.

2. What is the mission of the FBI?

3. Why did FBI Director Hoover believe it necessary to conduct extensive undercover surveillance?

4. Which constitutional rights did anti-Vietnam War activists believe the government was violating?

Expressing Your Reasoning

1. Should Bonnie and John Raines have participated in the burglary of the Media, Pennsylvania FBI office? Why or why not?

2. Is it right for government officials to conduct clandestine undercover operations? If so, why? If not, why not?

Key Concepts from History

What do the following have in common?

1. In November of 1872, Susan B. Anthony voted in Rochester, New York. Voting by women was against the law. Anthony believed that she had a right to vote. She was arrested, put on trial, and convicted of violating the law. The judge fined her $100, but Anthony declared in the courtroom that she would refuse to pay the fine.

2. On December 1, 1955, in Montgomery, Alabama, Rosa Parks refused to obey a bus driver's order that she give up her seat in the colored section to a white passenger, after the white section was filled. Parks was arrested for violating Alabama's racial segregation laws and prosecuted in court. She had deliberately taken a seat in the white section of the bus to protest racial segregation.

3. In late 1971, Daniel Ellsberg released to the New York Times and other newspapers the Pentagon Papers, a top-secret Pentagon study of U.S. government decision-making regarding the Vietnam War. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara commissioned the study from the RAND Corporation, a think tank formed to offer research and analysis to the United States armed forces. Ellsberg worked for RAND. In releasing the documents, he wanted to call attention to what he considered an unjust war that was going to continue and expand. He said, "I could no longer cooperate in concealing this information from the American public. I did this clearly at my own jeopardy and I am prepared to answer to all the consequences of this decision." He was prosecuted under the Espionage Act for revealing secret government documents.

Historical Inquiry

In 2014 John Raines lamented that the reforms adopted by Congress after the Media FBI burglary had become ineffective. He thought that the FISA court and congressional oversight committees no longer restrained government intelligence agencies as originally intended. He believed that the country had lapsed back to the conditions of 1971. Using online and other sources, test John Raines's hypothesis and compose a short essay in which you accept or reject it, using evidence to support your decision. To begin your investigation, the following search terms will be helpful:

-National Security Agency (NSA)

-Edward Snowden

-Glenn Greenwald

-The Guardian.

-Undercover operations

-FISA Court

Professors: Request an Exam Copy

Print copies available for US orders only. For orders outside the US, see our international distributors.