By Wayne Journell

Since President Trump’s election, the term “fake news” has been tossed around, not just in political circles, but increasingly within aspects of popular culture. As a result, defining exactly what fake news means in 2019 is difficult. At a basic level, fake news can be described as verifiably false information being presented as legitimate. The Russian attempt to influence the 2016 election through false social media posts is an example of actual fake news. This type of fake news presents a serious threat to democracy, particularly when research, such as Lazer et al. and McGrew et al.’s 2018 studies, suggests that both students and the general public have difficulty discerning legitimate from fraudulent information.

Since President Trump’s election, the term “fake news” has been tossed around, not just in political circles, but increasingly within aspects of popular culture. As a result, defining exactly what fake news means in 2019 is difficult. At a basic level, fake news can be described as verifiably false information being presented as legitimate. The Russian attempt to influence the 2016 election through false social media posts is an example of actual fake news. This type of fake news presents a serious threat to democracy, particularly when research, such as Lazer et al. and McGrew et al.’s 2018 studies, suggests that both students and the general public have difficulty discerning legitimate from fraudulent information.

Yet, it is the more colloquial definition of fake news popularized by President Trump that is potentially even more dangerous. Beginning with his victory in the 2016 Republican presidential primary and then throughout the subsequent general election campaign, Donald Trump used the term fake news to dismiss negative stories written about him by the “mainstream” media. Moreover, Trump has continued his defamation of the media throughout the start of his presidency. From December 2016, one month after winning the election, to the start of the following December, Trump tweeted about fake news over 150 times, and he continues to use the term on a regular basis to admonish news organizations with whom he disagrees, even when confronted with verifiable facts. From a political standpoint, the purpose behind Trump’s branding of mainstream media as fake news “has been to relentlessly turn questions of fact into questions of motive”.

By regularly blurring the line between fact and opinion, Trump has given license for people to dismiss information that contradicts their preexisting worldviews while simultaneously accepting verifiable untruths because they reinforce a broader ideology and/or sense of purpose. Moreover, this admonishment of the mainstream media has occurred alongside the rise of hyper-partisan media outlets, increasing political polarization, and a greater ability than ever before for people to self-select the media they consume. From a civic standpoint, one of the major ramifications of Trump’s appropriation of the term “fake news” is that it has drawn attention from actual fake news. Moreover, Trump’s success in getting people to automatically assume that news that contradicts their ideological beliefs is fake has made actual fake news more believable and, thus, more prevalent and effective. When individuals lose the willingness or ability to vet their political information, democracy is at risk.

For those who are not yet ready to write off American democracy as we know it, education may be the key to halting its decline. Although media literacy has been taught in K-12 schools for decades, the premise that factual information could be considered illegitimate simply because it contradicts one’s worldview presents new challenges for educators. Yet, education may be ground zero in the fight against fake news. Some studies, such as Kahne and Bowyer’s 2017 research paper, suggests that the more formal education students receive on how to identify fake news, the more likely they are to seek reliable sources of information. However, in order for K-12 education to truly make a dent on the effect of fake news, students must move beyond simple heuristics designed to determine whether sources are valid; rather, students need to develop an understanding of why fake news is effective, why it is problematic, and how they/we are culpable in its dissemination.

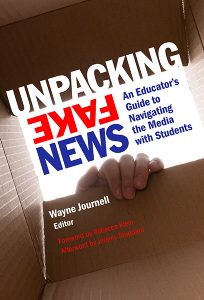

Featured Image: “American News” public domain via Pixabay.

Wayne Journell is associate professor and secondary education program coordinator at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. He currently serves as editor of Theory & Research in Social Education and is a past recipient of the Exemplary Research in Social Studies Award from the National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS).