Author, Improving Online Teacher Education: Digital Tools and Evidence-Based Practices

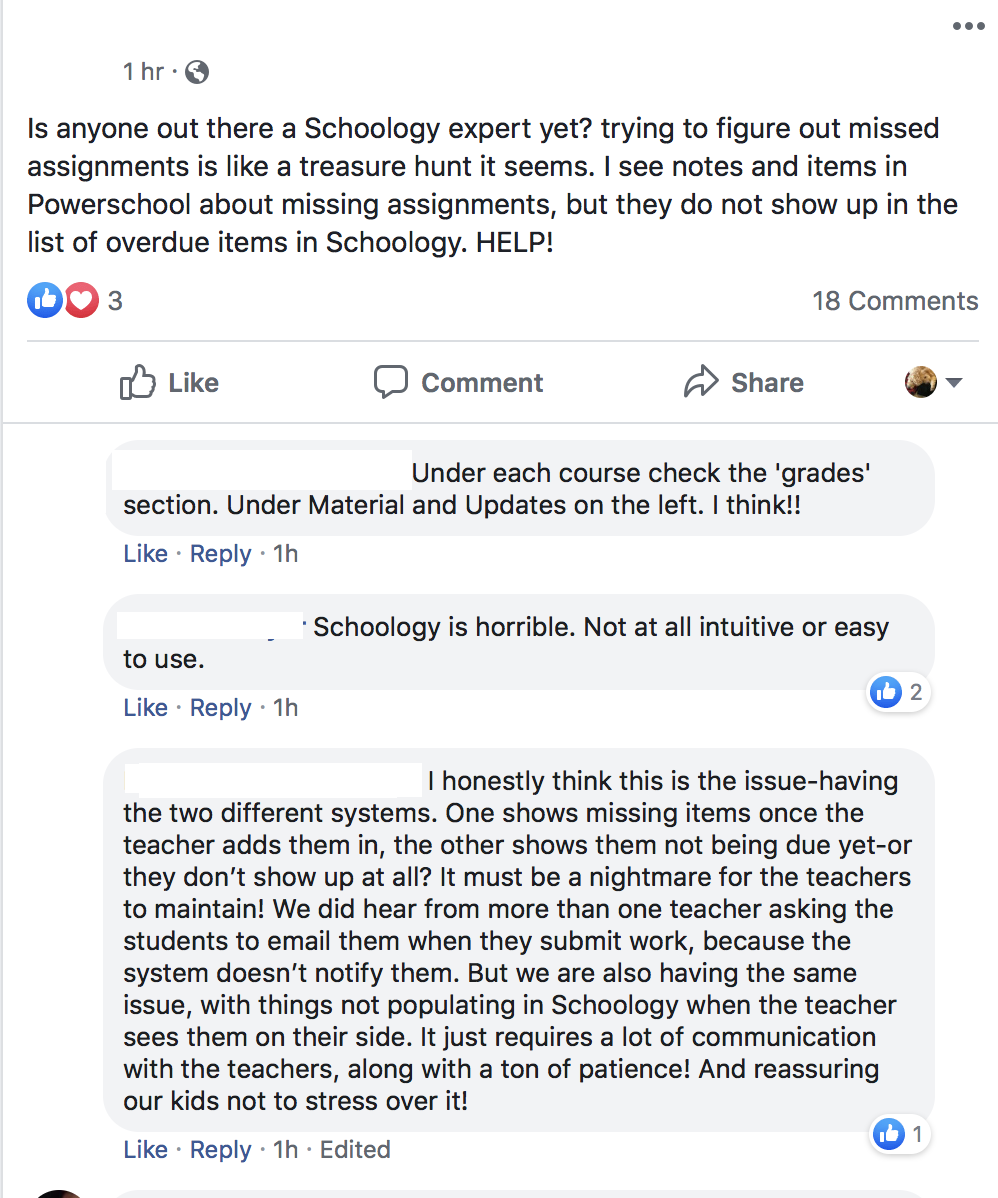

I’m a parent of a sixth-grader and like most families with school-age children, my husband, son, and I are navigating the emergency remote learning experience that is our current reality. Similar to the concerns expressed in the public Facebook thread shared here, I’ve found it difficult to support my son with at-home learning because I do not have access to all of the content posted by his teachers. Luckily, he is adept at navigating his work, but I can’t help but wonder about students who never reach the learning activities because they spend so much time trying to access the work.

I’m also a former public-school teacher and a current university professor who has been teaching, studying, and publishing on the topic of reading and writing in digital spaces for twenty years. Like universities around the world, my institute made the quick transition to campus-wide online classes and as the semester ends, the administration is grappling with tough decisions about the future. Effective online instruction is not easy. It takes training and trial and error. Overall, it is a long-term time and financial investment in educational practices that leverages digital tools in ways that support thoughtful learning.

I taught my first university online course in teacher education in 2003 when dial up was the only option and my graduate students and I communicated synchronously by typing in a small chat box. Although not a seamless experience, I saw the promise in providing online learning opportunities for college-age students and have continued to teach fully online and hybrid courses ever since. Although technology has evolved dramatically over the years, providing affordances that allow for interactivity and collaborative learning, not much has changed in the way of preparing classroom teachers and university instructors to teach in digital environments. In fact, I would argue PK-12 schools and universities remain stagnant, allowing technology-integrated instruction to happen only when teachers choose to make it a priority.

This is worrisome because I am hard-pressed to believe there will be any scenario in the fall that does not include some type of online teaching component. For that reason, it is imperative for all schools and universities to up their game now by strategically approaching how they prepare faculty to design and implement effective online instruction. These activities cannot take place in a vacuum. Instead they must be part of a public relations campaign aimed at convincing stakeholders that the education provided in the fall will be worthy of students’ time as well as tuition and tax dollars.

I recognize the need to plan for several scenarios. I also recognize and commend the hard work educators at all levels have put into translating their traditional face to face instruction to online delivery. Yet what is acceptable to many now, will not be acceptable in the fall. In the frenzy of emergency remote teaching, sound pedagogical practices have been dismissed and replaced with an overabundance of teacher-centered direct instruction. For instance, I’ve observed my middle schooler watch videos for his Japanese class, play digital games in math, and complete digital worksheets, lots and lots of worksheets. In the past nine weeks, he has interacted sparingly with his teachers in real time and has never collaborated on school work with classmates.

Ask any expert in the field and they will tell you that online teaching does not mean teaching brick and mortar coursework using a video conferencing tool, but instead making intentional design choices grounded in learning objectives. Students’ strengths and areas in need of improvement must then be considered along with appropriate assessment measures followed by the careful selection of digital tools. The process is time-consuming.

So how do PK-12 schools and institutes of higher education build their PR campaigns related to the quality of online instruction? Three approaches are shared below:

- Leadership must determine a set of instructional expectations to be followed by all faculty. These convey decisive statements such as where materials will be curated for every class (e.g., LMS), from whom and how information will be communicated to different stakeholders, and parameters for student engagement. These expectations do not infringe on faculty’s academic freedom. Rather, they lay a groundwork to build a cohesive experience, one that removes logistical uncertainties (e.g., where do I find my English homework?) and allows teachers and students to focus on learning. Remember, students are taking multiple classes and learning from multiple teachers. Consistency across grade-levels and courses of certain aspects of online teaching will support seamless navigation.

- Leadership must require all faculty to complete training in online course design. This means having the technical knowledge to utilize the chosen learning management system and basic understandings of how to frame instruction using effective online pedagogical practices. Collaboration and interactivity should be prioritized and while digital tools should be considered, they should not be the focus. Instead, they should be selected based upon how best to achieve learning goals. Although the extent of expertise will differ, it is critical that the message be conveyed to stakeholders that online instructional practices have been taken seriously.

- Leadership must support students. Online learning requires time-management and digital literacy skills, both not taught nearly enough to prepare students of all ages for the demands of online learning. True, many students have basic understandings of how to use digital tools for their classroom work, especially if they learn in a 1:1 setting. However, effective online instruction requires students to interact and collaborate with resources in ways that require critical thinking and reflection upon their own learning. It also requires students to initiate conversations with teachers when they are confused by content, a much more difficult task when not in the same room. Leadership must consider how they will prepare students to be online learners.

There is a lot of uncertainty about what schools will look like this fall, yet one thing we know for sure is that technology can be leveraged to provide learning opportunities whether it be through emergency remote teaching or thoughtfully designed effective online instruction. As the academic year ends, we surpass the temporary solution to this spring’s disruption in face to face instruction. Now is the time to prepare for what is to come in the fall and with a cohesive PR plan in place, schools and universities can trumpet positive outcomes.

Featured image by Mudassar Iqbal Pixabay

Comments

I agree with your guidelines for administrators. Prior to covid-19, I had a discussion with my son’s middle school assistant principal about teacher use of Schoology. Some teachers put all of their content on it, others did not use it at all. At that time, the assistant principal told me that the administration couldn’t require that the teachers use the learning management system. Of course, a few months later, all classes had migrated online-but there was a vast difference between the ways teachers used it. A few of his teachers had weekly assignments that were published on Sunday and due by Friday. Others, would post things at all different times and set the due date for three days after the item was published. It was very difficult for my son to keep track of the different systems. I also agree that it is imperative for teachers to receive training on online instructional design. They need to think about how their students will access the material.

I served as co-instructor for a fully online Master’s course being offered for the first time on a 7.5-week calendar in March-April 2020. The course had been fully and elaborately designed by the lead instructor during the previous 9-12 months, with the help of a small team of online course designers and IT assistants and within a well-established framework for online offerings at our large public university. Sounds like an easy gig, right?

In hindsight, the course was successful. But serving as co-instructor, leading 13 of our 26 students, was a huge amount of work–much more so than any of my many prior face to face courses were. I was willing and even eager to provide prompt, clear and encouraging feedback on each of my students’ 3 weekly written assignments, and they expressed appreciation throughout. In a sense, my feedback and that of the other instructor were the only real “teaching” that we did–everything else was what I would call “structured self-instruction” [read the assigned readings, write a summary of the readings, find some additional readings relevant to your particular interests, summarize those readings, read an assigned peer’s summaries and provide peer feedback, repeat, repeat]. Obviously, this structure was very demanding for the students, especially since March-April 2020 was a totally disruptive period for everyone. The success of the course I attribute mainly to the persistence and commitment of the students and to their technological savvy, connecting asynchronously from time zones stretching from eastern China and Seoul to Kuwait City.

So, four take-aways for me concerning online instruction, much of which I think applies to students of every age:

1. Online can be very demanding for teachers and for students. Instructors deserve lots of load credit and may need 24/7 significant support during course design, continuing through course delivery and after-action analysis. Old fashioned professional development half-day workshops will not do. Also, it helped me a great deal to have a colleague/co-instructor with whom to talk things over and work out bugs in real time.

2. For your students to succeed, they will benefit from more or less continuous personal encouragement and coaching. Adjust course demands downward to make their first few online learning experiences successful for all (not just for the super-achievers).

3. Include a capstone product as a final assignment that each of your students will build toward throughout the course. Have them share partial drafts with you and with a peer as the course proceeds, so that the learning community can develop a shared sense that We are all learning different but related things and that each of us is drawing on new learning, prior knowledge and personal interests to create a distinctive work in progress.

4. Take care of yourself. Set healthy boundaries–times of the day or week when you will turn off your laptop and separate yourself from the ceaseless opportunities to be “on”. Talk regularly and mutually supportively with a colleague, ideally a co-instructor who understands the particulars of the course, the systems and this unique group of students. Sleep with your smartphone off, banished to another room.

Remember, it gets better.