By: Young Whan Choi

Young Whan Choi (he/him) has been a teacher in South Korea, New York City, Providence, RI, and Oakland, CA, during which time he developed expertise in project-based learning, curriculum design, and culturally relevant teaching. Currently, he teaches the next generation of social studies educators at UC Berkeley. His new book, Sparks Into Fire: Revitalizing Teacher Practice Through Collective Learning, publishes July 2022. He has written for various publications including the Washington Post’s AnswerSheet, EdSource, The East Bay Times, and UCLA’s Xchange journal. He produces and hosts The Young and the Woke podcast.

The following is excerpted from Sparks Into Fire, and originally appeared at Next Generation Learning Challenge. It is reposted with permission.

One summer, my colleague Lizzie Humphries and I were faced with a dilemma: how to get teachers to try something that many of them had not experienced when they themselves were students. While traditional civics instruction is passive, as in “Write an essay in which you explain what the Framers meant by checks and balances,” we were leading a PD with the goal that teachers would have their students make real change through a civic action project, not simply learn about how government worked in theory. Instead of telling the teachers to design a unit with the three elements of OUSD’s civic engagement framework—analyzing issues, taking action, and reflecting—we were going to have them experience it firsthand through participating in their own project.

To hype it up and bring a little levity to our summer PD, I recorded myself intoning over the Mission Impossible theme music,

Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to improve the lives of teachers in Oakland. As always, should you or any of your team be caught or killed, the civic engagement coordinator will disavow any knowledge of your actions. This tape will self-destruct in five seconds. Good luck.

The teachers perked up. They set down their morning cups of coffee and tea, looked at one another, and smiled. It was game on.

We began with the question, “What are challenges that OUSD teachers face that are not directly related to students?”

We chose this question because we wanted teachers to think beyond complaints about students and to encourage them to consider other work-related challenges. In small groups, teachers generated questions that they wanted to ask a colleague. We then selected a narrow set of questions, which all the teachers used to record an interview with a colleague. At the end of the interviews, each teacher submitted a compelling quote. By the end of the activity, we had 35 quotations about the challenges teachers in OUSD face, which Lizzie and I proceeded to code by theme.

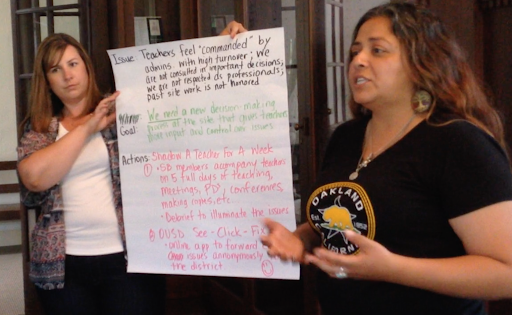

The next morning, teachers looked at the quotations and the data trends from the interviews and noticed that the area of greatest challenge for teachers was management issues at their site or at the district level. One quotation encapsulates the spirit of many.

It’s about real collaboration between district and schools… Not just mandating us to do something or starting off the year with a listening circle that occurs once and just serves the facade of collaboration.

There was real pain and frustration expressed in those interviews. They longed for something better; seeing that many of their colleagues across the district felt the same way was a powerful form of validation.

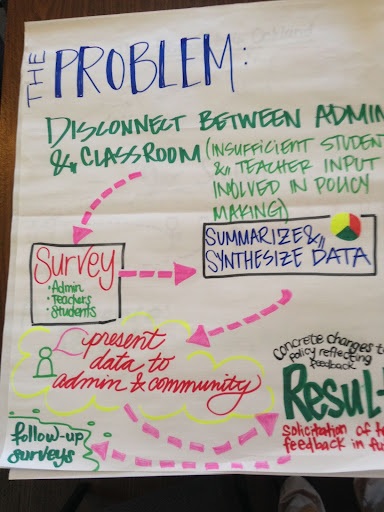

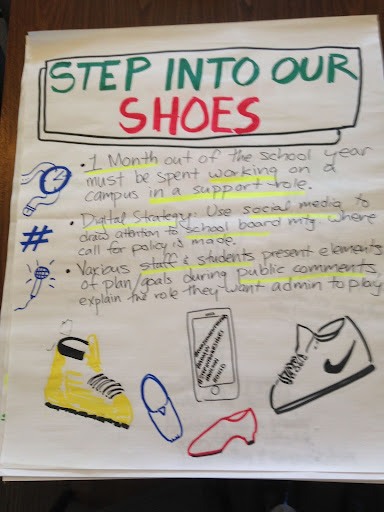

Teachers then gathered in small groups for 30 minutes to read the interview quotes and come up with ideas for how to address the specific concerns with management, which were named in the interview data. For an added measure of authenticity, I had invited their teachers’ union president to come and listen to them. They presented their ideas to her, which included: having central administrators spend a day per month at a school in a non-evaluative support role; developing faculty councils at every school site; organizing a welcome luncheon to develop community between administrators and teachers; and demanding staff, parent, and student input into the hiring of administrators.

Had there been more time, teachers could have implemented some of their ideas and then reflected on the impact of their actions. Instead, for reflection, we asked teachers to consider the following two instructional questions: What academic skills and knowledge did you rely on to complete the interview and action project? What cultural, social, and emotional skills and knowledge did you rely on to complete the interview and action project?

For the teachers, the point of the reflection was for them to think about what they would have to do instructionally to support their students in a meaningful civic action project. But something else emerged from the process. Teachers were fired up and passionate. There was laughter and joy.

One teacher recounted in a survey,

Creating our own action plan for teacher challenges based on interviews and the analysis by our leaders. So cool. Felt empowered. Understand how this kind of lesson would engage students if the lesson is designed well.

Teachers “felt empowered” because they had the chance to collaboratively address an issue that mattered to educators in OUSD. I remember one teacher raising her hand and saying that she knew this was an exercise, but she didn’t feel like she could just stop working on these issues. And that’s exactly how we want our students to feel—so passionate about what they are doing that the work and thinking and creating extends beyond the confines of the classroom.

The experience reaffirmed my belief that if we want students to be deeply engaged in learning, teachers need to have those kinds of experiences, too. In contrast, if we continue to “train” teachers through narrowly prescribed approaches, reinforcing their own socialization from when they were students, then we should expect similarly mind-numbing instruction in our classrooms where a small number of students speak in class and only when prompted by their teachers. Improving our schools will require powerful changes to how we approach teacher learning.

Reprinted by permission of the Publisher. From Young Whan Choi, Sparks Into Fire: Revitalizing Teacher Practice Through Collective Learning, New York: Teachers College Press. Copyright © 2022 by Teachers College, Columbia University. All rights reserved.

All photos courtesy Young Whan Choi