An earlier version of this blog was posted on the Motivation in Education SIG site

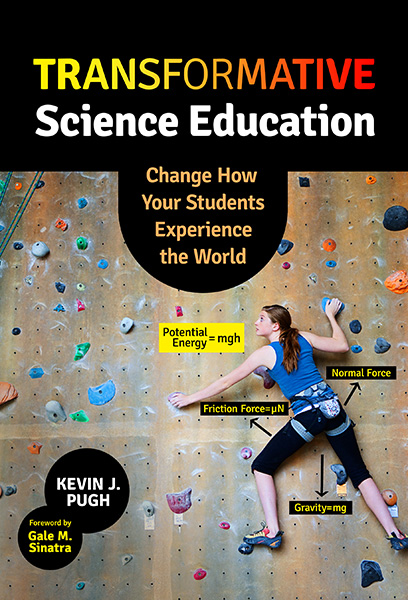

Kevin Pugh is the author of Transformative Science Education: Change How Your Students Experience the World and professor of educational psychology at the University of Northern Colorado.

Hogwarts – the school of witchcraft and wizardry in the Harry Potter books – has its share of pedagogical problems. Professor Binns could use a dose of Interest Theory, Hagrid should attend a school safety seminar, and Snape really needs to read The Challenge to Care in Schools. Then there’s Professor Umbridge. That pink assassin of education who neuters the transformative power of education by teaching theory. Yet, when you think about it, when it comes to neutering the transformative power of education, we’re all Professor Umbridge.

Some background for those who haven’t read the Harry Potter books or seen the movies (I’m giving you a pass). Dolores Umbridge makes her appearance in Harry Potter and the Order the Phoenix. She is the new Defense Against the Dark Arts teacher and focuses her instruction exclusively on the theory of magic. No relevance. No practical application. No skill development. Just abstractions and bookwork. By doing so, she effectively renders the course knowledge inert.

Now, it turns out (spoiler alert!) there is a nefarious purpose behind the pedagogy of Professor Umbridge. She is afraid Dumbledore, the Headmaster of Hogwarts, is raising an army to rebel against the Ministry of Magic. She also loves having power over others. Thus, she wants her students’ learning to be useless because she wants them to be helpless. So evil!

By and large, real-world teachers are not evil. In fact, I love teachers. I think they are the best people on the planet. And yet…and yet they often practice the pedagogy of Umbridge.

Education (at the institutional level) has a primary focus on teaching theoretical ideas and abstractions. Real-world application is hoped for but not the focus. Unfortunately, this approach results in learning being non-transformative for most students because developing applied knowledge and making connections to everyday experience is really hard. In our own research in science classrooms (e.g., Pugh, Bergstrom, Krob, & Heddy, 2017; Pugh, Linnenbrink-Garcia, Koskey, Stewart, & Manzey, 2010, we’ve found that, even with good teachers, only about 10-15% of the students deeply apply their in-school learning to their out-of-school experience. As I like to joke, the Las Vegas slogan applies all too well to classrooms: what happens here stays here.

The pedagogy of Umbridge is based on this simple principle: the transformative power of education can be sterilized by teaching pure theory without a sustained focus on putting theory into practice. Don’t get me wrong. I am not saying theory is bad. Quite the contrary. Theory is extremely powerful. I suspect Dumbledore is a powerful wizard precisely because he deeply understands the theory of magic. But most of us aren’t Dumbledore. When theory is taught in abstraction, we can’t translate into practice on our own. Instead, the abstraction becomes a substitute for real-world experiencing.

The great educator John Dewey recognized this problem over a century ago and presented it in terms of a metaphor I love and have written about before. In this metaphor, Dewey compared the curriculum to a map. A map is empowering. It guides our experience and enables us to undergo more fruitful journeys. Likewise, the ideas that comprise the curriculum (i.e., the theory) can guide our experience in the world and help us have unique journeys of meaning and discovery. However, Dewey cautioned, “The map is not the substitute for a personal experience. The map does not take the place of an actual journey” (Dewey, 1990/1902, p. 198). Maps are fun to look at, but if studying the map becomes a substitute for using it to have an actual journey, something has gone wrong.

The pedagogy of Umbridge substitutes the map for the journey. Theory of magic should be a guide for confronting Dark magic in the real world. Instead, theory of magic is substituted for real-world experiencing. This is it what happens in many of our classrooms. Learning about science becomes a substitute for actually using science to see and experience the natural world in profound new ways. Learning about history becomes a substitute for actually using history to understand the events our days. And so on.

Is there any hope? Can we cast off the pedagogy of Umbridge and make learning more transformative? I have spent my research career asking these questions and trying to come up with solutions, primarily within the domain of science education. In so doing, my colleagues and I have developed transformative experience theory. The good news is that, yes, we can make learning transformative for far more students. My colleagues and I certainly don’t have all the answers, but we have developed an anti-Umbridge pedagogy which we refer to as the Teaching for Transformative Experiences in Science (TTES) model. This model is described in detail in a newly released Teachers College Press book, Transformative Science Education: Change How Your Students Experience the World.

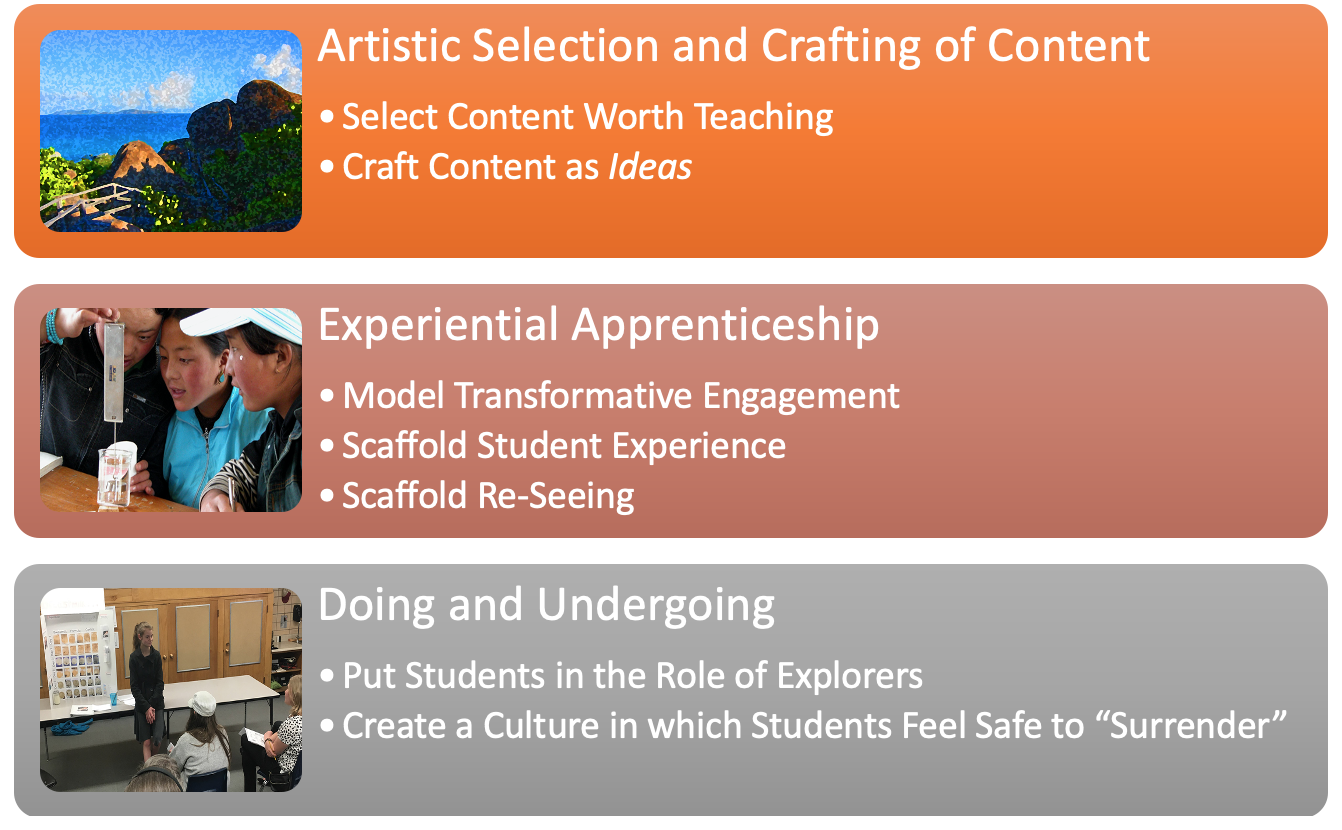

In addition to describing the TTES model, this book includes rich classroom vignettes of the model in action and “try it out” guides for applying the model. Below I provide an overview of the three design principles central to the TTES model.

Design Principle 1: Artistic Selection and Crafting of Content

When Van Gogh painted Wheatfield with Crows, he was deliberate about what to include in the composition. Wheatfields. Stormy skies. Crows. These had paradoxical meaning to Van Gogh. Representations of the health and beauty he found in nature, but also symbols of the loneliness and mental turmoil he suffered. They provide the foundation for a powerful painting juxtaposing beauty and turmoil. Van Gogh was also deliberate in the style he used to craft these objects. His famous use of bold brushstrokes and intermixing of vibrant and dark colors works to further evoke a sense of tumultuous beauty and vivacious loneliness. This artistic process of selection and crafting is what makes Wheatfield with Crows a masterpiece.

Likewise, teachers can be masters of their craft by artistically selecting and crafting content. Not all content is worth teaching and some content has particularly powerful affordances. One way teachers can make learning transformative is by selecting powerful content. Among other things, this involves selecting content with the potential to be ideas. Ideas are anticipatory. That is, they awaken anticipation and compel us toward action. They contain the seeds of wonder and the sublime.

Once potentially powerful content has been selected, it has to crafted for it to realize it’s potential as an idea; as a compelling possibility that needs to be acted upon and tried out in the world. Teachers can craft content by fostering anticipation, emphasizing the value of the content in everyday experience, presenting compelling metaphors, and evoking a sense of wonder, suspense, and the sublime. For example, I like this statement made by Walter Lewin, a renowned MIT physics professor,

All of you have looked at rainbows, but very few of you have ever seen one. Seeing is different than looking. Today we are going to see a rainbow. Your life will never be the same. Because of your knowledge, you will be able to see way more than just the beauty of the bows that everyone else can see. (quoted in Rimer, 2007, para. 29)

Now there’s a statement that sets the stage for artistically crafting content (e.g., Snell’s law, refractive index) as a transformative idea.

Design Principle 2: Experiential Apprenticeship

In an apprenticeship, a master uses modeling and scaffolding to help apprentices develop real-world skills. In an experiential apprenticeship, teachers use modeling and scaffolding to help students develop ways of experiencing the world through the content.

Modeling, in the context of an experiential apprenticeship, involves sharing personal transformative experiences with students. Teachers share their own experiences of seeing the world through the lens of the content and express their enthusiasm for doing. I once had a geology professor who often started class by showing his latest picture of a landform or road cut he found interesting. He did so with such gusto that his passion was contagious. I started seeing geology everywhere. My learning was transformative.

Scaffolding, in the context of an experiential apprenticeship, involves supporting students in their efforts to see and experience the world through the lens of the content. Such scaffolding can involve helping student identify opportunities they have to “re-see” the world through the lens of the content, providing opportunities for students to share their re-seeing experiences, and supporting students as they move from surface- to deep-level re-seeing. Scaffolding can also involve using boundary-crossing objects like mobile technologies to integrate in-school and out-of-school experience.

The value of scaffolding experience is illustrated in the results of a collaboration my research team did with Hayden (pseudonym), a sixth-grade earth science teacher. During a unit on weather, Hayden had his students read and research a case study on the Santa Ana winds. Unfortunately, the students treated this assignment as bookwork without relevance to their everyday lives. They were learning the content but not “having the journey.” We discussed ways to support the students in making connections to their own lives and decided it would be smarter to have students research their own weather experiences instead of the Santa Ana winds. Hayden first provided time in class for students to share their own wild weather experiences and practice re-seeing these experiences through the lens of meteorology content. Then we developed case studies out of the students’ experiences and had them research these experiences in more depth. Researching their own experiences made all the difference. As one student said, “It did matter, ‘cause you could make connections, and you could go back, and yeah, it was cool. Like the blizzard one, I could make connections to my life” (Pugh et al., 2017).

Design Principle 3: Doing and Undergoing

Transformative experiences require both doing (taking action) and undergoing (being acted upon). Translated to education, this means students need opportunities to engage in authentic activities of doing and be explorers of a domain. They also need a culture in which they feel safe to passionately engage and “surrender” to the experience.

The real world of science involves discovering, creating, serving, and adventuring. Unfortunately, many science classrooms practice the pedagogy of Umbridge and focus primarily on learning science theory. Authentic activities of doing are neglected. Fortunately, there are a number of models that put students in the role of being science explorers. Such models include inquiry learning, project-based learning, service learning, and expeditionary learning. As part of her middle school experience, one of my daughters had the opportunity to conduct an inquiry into causes of coral bleaching, get scuba certified, and travel to Florida to participate in actual coral restoration. This was a genuine science experience of doing led by a teacher who knew how to make learning transformative.

Creating a culture in which students feel safe to undergo—that is, surrender to the learning experience—is also necessary for learning to be transformative. One way teachers can create such an environment is by teaching and fostering mindfulness. Mindfulness is an ability to attend to the present moment without being distracted by thoughts, emotions, or judgments (Kabat-Zinn,2012). Teaching mindfulness can help students clear and focus the mind, become fully aware, and activate a flow state; thus preparing them to undergo. A second strategy is to establish a mastery goal environment; that is, an environment that focuses on individual learning while deemphasizing social comparison and public evaluation, values effort over high ability, treats mistakes as part of the learning process, and highlights the meaning of content over the assessment of content. A third strategy is to support autonomous motivation by creating an environment in which students can feel a sense of autonomy, competence, and belonging.

The pedagogy of Umbridge seeks to disempower students by separating learning of content from its relevance in everyday experience. We can rebel against this pedagogy by teaching for transformative experiences. A colleague of mine, who was such a rebel, one had a fourth-grade student of his say, “Now when I don’t have anything to do, I look at a rock and try to tell its story. I think about where it came from, where it formed, where it’s been, what its name is…I used to skip rocks down at the lake but now I can’t bear to throw away all those stories!” (Girod & Wong, p. 211-212). Now that’s using the curriculum to have a journey. That’s transformative learning. Umbridge would not be happy.

References

Dewey, J. (1990). The school and society and the child and the curriculum. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press (original work published 1902).

Girod, M., & Wong, D. (2002). An aesthetic (Deweyan) perspective on science learning: Case studies of three fourth graders. Elementary School Journal, 102, 199-224. doi:10.1086/499700

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2012). Mindfulness for beginners: Reclaiming the present moment of your life. Sounds True.

Pugh, K. J. (2020). Transformative science education: Change how your students experience the world. Teachers College Press.

Pugh, K. J., Bergstrom, C. R., Krob, K. E., & Heddy, B. C. (2017). Supporting deep engagement: The Teaching for Transformative Experience in Science (TTES) Model. Journal of Experimental Education, 85, 629-657. doi:10.1080/00220973.2016.1277333

Pugh, K. J., Bergstrom, C. M., & Spencer, B. (2017). Profiles of transformative engagement: Identification, description, and relation to learning and instruction. Science Education, 101, 369-398. doi:10.1002/sce.21270

Pugh, K. J., Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., Koskey, K. L. K., Stewart, V. C., & Manzey, C. (2010). Motivation, learning, and transformative experience: A study of deep engagement in science. Science Education, 94, 1-28. doi:10.1002/sce20344

Rimer, S. (2007). Academic stars hone their online stagecraft. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/19/education/19cnd-physics.html

Featured image used with permission from: https://flic.kr/p/sGLcB

Comments

This is such an interesting take on teaching pedagogy. As a huge Harry Potter fan myself, I appreciated the metaphor to illustrate the point that so much learning is not applicable to the real world. Reading this made me wonder about how the way we think of teaching and how that affects the way we actually teach in practice. We often have a mental image, an idea of sorts, that teaching is intended to be one teacher at the blackboard lecturing while students simply listen and absorb information. It is part of our “grammar of schooling.” I feel that is the way we often imagine teaching in our heads, and as a result, I wonder if this might affect our practice.

As a fascinating side note, Dr. Ebony Bridwell-Mitchell proposed a series of changes to the way we analyze the grammar of schooling, which might have some implications for this issue. Dr. Bridwell-Mitchell suggests using an institutional analysis model to analyze our school system. She suggests it may be useful for a number of education issues, including pedagogy. Our conception of the classroom is so deeply ingrained and institutionalized that I’m sure it would be applicable to a study like one proposed in this article. To read more about Dr. Bridwell-Mitchell’s idea, here is the link to her article: http://www.ajeforum.com/more-than-metaphor-what-we-miss-in-the-charge-to-change-the-grammar-of-schooling-by-dr-ebony-n-bridwell-mitchell/?unapproved=59988&moderation-hash=0c95f1bf34467bb5accc7f989ccdb5ba#comment-59988