By: Young Whan Choi

Young Whan Choi (he/him) has been a teacher in South Korea, New York City, Providence, RI, and Oakland, CA, during which time he developed expertise in project-based learning, curriculum design, and culturally relevant teaching. Currently, he teaches the next generation of social studies educators at UC Berkeley. His new book, Sparks Into Fire: Revitalizing Teacher Practice Through Collective Learning, publishes July 2022. He has written for various publications including the Washington Post’s AnswerSheet, EdSource, The East Bay Times, and UCLA’s Xchange journal. He produces and hosts The Young and the Woke podcast.

This blog post originally appeared at Next Generation Learning Challenge, and is reposted with permission.

The sun was still high in the sky as I pulled a cooler laden with ice up a grassy knoll to where my co-instructor Lizzie Humphries awaited. Over the next 30 minutes, our students—15 aspiring social studies teachers—arrived and created a circle of blankets and beach chairs. From my seat, I could scan the blue sky, the clusters of bay trees and coast live oaks, and the faces of my students, filled with a bittersweet mix of sadness and joy that accompanies a significant transition.

It was our last History Methods class of the year. To start, I shared a statistic—not the typical depressing report of what’s wrong with education like often cited rates of teacher turnover, learning loss, or mental health. Instead, I shared the promising news that life expectancy rates for Latinos are higher than for Whites despite the structural inequities that Latinos face like poverty, difficult work environments, and less access to healthcare.

What accounts for this startling fact? Some medical experts believe that family and social connections are one factor that explains this “mortality paradox.” If this is true, then these human to human ties, where they exist, are literally keeping people alive longer.

The power of relationships extends to the field of education where researchers like Anthony Byrk have identified relational trust among adults as critical to the success of schools. Neuroscientists like Mary Helen Immordino-Yang have studied how the areas of our brain responsible for emotional processing are actively engaged when we are learning. In other words, the mushy stuff like relationships and emotions are a vital part of teaching and learning.

And yet, the vast majority of pre-service programs and in-service professional development do not attend enough to the relationships that undergird learning. Yes, we know that it’s important to have “ice-breakers” and “getting to know you” activities. But even if we do these community building activities, we generally stop short of thinking of them as part of our pedagogy. In most schools of thought, pedagogy entails cultivating the skills of a particular discipline like, in the case of history, teaching how to source a document or using evidence to make an argument.

We need a pedagogical practice that is expansive—that embodies the best of what we know about how to teach a particular content area while also attending to the culture that supports caring, respectful relationships. Learning is an alchemy of what are often thought of as separate elements: skill acquisition, content understanding, and relationship to others engaged in the work.

Lizzie and I have facilitated a human-centered approach to teacher learning, and I describe the principles and practices of this approach in a forthcoming book: Sparks Into Fire: Revitalizing Teacher Practice Through Collective Learning (Teachers College Press). Two themes from the book can help us foster a supportive learning community: we need to tell stories about our purpose as educators and we need to model vulnerability.

Telling Stories of Purpose

To prepare for the first class, we gave the following prompt: Choose an image of (or object that relates to) a given or chosen ancestor(s)—1 or 2 people who have influenced you. Bring that image/object to class (ideally, something that can be kept in the class). Prepare to share: How do these people connect to who you are today, especially related to who you want to be as a history teacher?

Lizzie and I kicked off the sharing by introducing an ancestor who shaped us as educators. Then our student Alicia Lopez volunteered to go next. She brought in a picture of her with five generations of women on her mother’s side. Pointing to her great-great-grandmother and great-grandmother, she teared up and revealed that though they had passed they are still guiding her. As she later told me, “None of the women in my family have ever gotten more than a high school education so I am very proud of this achievement and I know that my ancestors are too.”

For the next hour and a half, we heard personal stories that helped us understand the deep purpose that motivated each of our students. These stories might seem out of place in a traditional teacher education course, but that’s exactly the point. We have long stripped away the relational elements of teaching, so it will take intention and care to insert them back in. And when in doubt, the voices of our students remind us of why the human dimension is critical. Here is some of the feedback from our first class:

I enjoyed getting to know everyone better and learning about their histories!

I LOVE this. This is the first time that History is together and I LOVE it! Thank you for this space, I really loved hearing from my peers…

The opening was POWERFUL. Sharing and holding space like that, first time in person as a History pathway, grounded our work in the weight of what we are embarking upon.

I appreciated how we started with our own ancestral history. It really solidified the importance of us as living texts within this class.

Sharing these stories normalized that our class was a place where we could be open with each other. And this vulnerability was not merely an attempt to create a kumbaya experience. Teaching is hard, soul-searching work. Teachers need places where they can share their struggles in the classroom and their peers can offer a nurturing mix of support, curiosity, and critique.

Modeling Vulnerability

Throughout the year, Lizzie and I tried to model what it looks like to be vulnerable as teachers. Following our ancestor sharing, Lizzie and I taught a three-day mini-unit on the Black Panther Party, which culminated in a City Council simulation where the students role-played council members who deliberated the merits of a resolution to create a statue of Huey P. Newton in front of the Alameda County Courthouse in California.

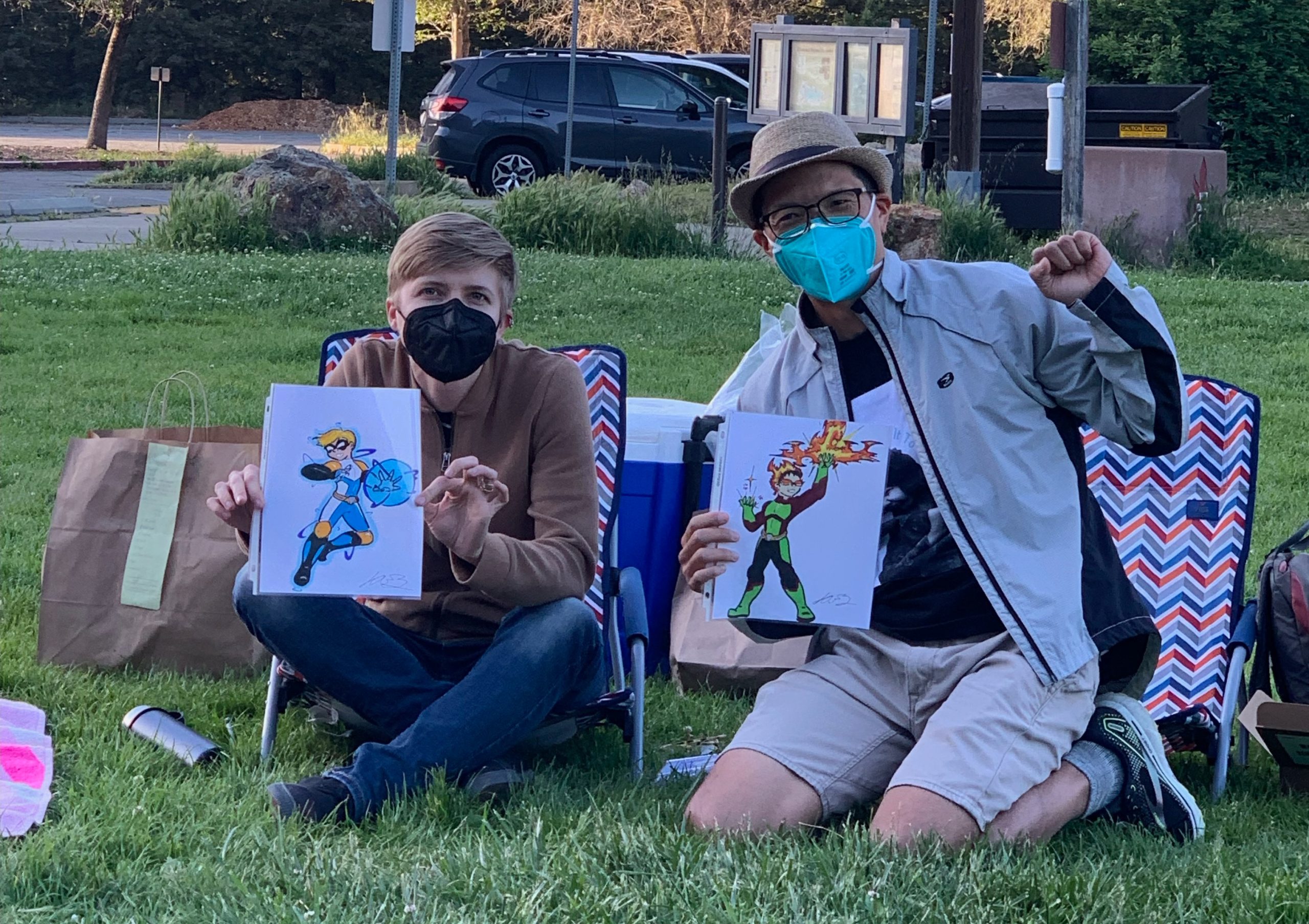

Lizzie and Young Whan with their superhero avatars drawn by their student and artist Jonah Arreola-Burl. (Photo by Itzel Calvo Medina)

This unit was designed as an example of their final semester assignment, so they could experience firsthand what they were supposed to design and implement in their student teaching placements. We attempted to bring together pedagogical practices related to backward designing units, teaching complex texts, supporting language and literacy development, discussing controversial topics, and cultivating civic dispositions.

At the same time, we modeled how to reflect openly on our teaching practice. We shared our own challenges in the planning, explaining why we had made certain changes from the previous year, and asked for our students’ constructive feedback. As one student wrote, “Thank you for being honest with your choices and changes, and Iistening to our critiques. It makes me feel like I trust y’all as teachers and as community members. I would want this transparency to be the model for all of my…classes. Makes me feel like I’m in a horizontal space, not in a vertical hierarchy.”

At the end of the day, Lizzie and I do have power over our students in the form of grades that can impact their future. Still, we level the conversation when we stay open to our students’ feedback. At the end of each class, for example, students filled out a simple survey answering two questions: What worked for you in this evening’s class? What didn’t work for you, or what can we do in future classes that will support your learning?”

As students filled out the survey, we would narrate some of the trends that we saw in the feedback to make clear that we were hearing their feedback and we made sure to follow up on their feedback in the following class…with one glaring exception.

After our second class, a student offered, “I think everything has been going well so far. Everything is solid for me. (maybe a pizza party???).” We read that comment aloud, which brought laughter and then inspired a series of copycat comments in subsequent surveys. Requests for pizza appeared six times that fall; the demand only grew in the spring. So finally, for our final class, we gathered at a local park for the long anticipated pizza party.

We celebrated one another by writing an appreciation note to each student in the classroom. Each student received 17 cards—physical reminders of the emotional bonds that we had created this year. It was the perfect way to bring closure to a powerful year of professional learning, a year of learning that would not have been possible without the relationships and vulnerability that were at the heart of our pedagogy.

Featured photo courtesy Young Whan Choi