By: Susan Zoll

Susan Zoll is an author, Montessori researcher, and educator who serves on the American Montessori Society’s Research Committee. She is the coauthor of Effective Literacy Assessment in the Montessori Classroom (Teachers College Press, 2025), Powerful Literacy in the Montessori Classroom (Teachers College Press, 2023), and Implementing the Montessori Method (forthcoming 2026). Learn more about her work at www.dr-susan-zoll.com.

Are you worried your child may experience the summer slide? There are two research-based strategies any parent can add to their schedule of activities that can offset potential learning loss this summer: book reading and conversation. It’s that easy… and here’s why.

We’re already well aware of the dismal reading results from our country’s education report card, better known as the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP 2024). Less than 31% of our country’s fourth- and eighth-graders are reading proficiently. And for those students who are already struggling, time away from learning opportunities can negatively impact their ability to “catch up” academically. This learning loss is often referred to as the summer slide.

In recent years, many states have passed legislation requiring schools provide reading instruction based on current research. This has influenced school districts’ curriculum selection, instructional practices, and assessment tools. In addition to what happens in classrooms, families can also play a pivotal role in helping children become competent readers—without requiring any special curriculum or workbook review at the dinner table. Rather, an intentional focus on children’s language development—vocabulary and background information related to topics that are of interest to them—can be a vital support to positive reading outcomes.

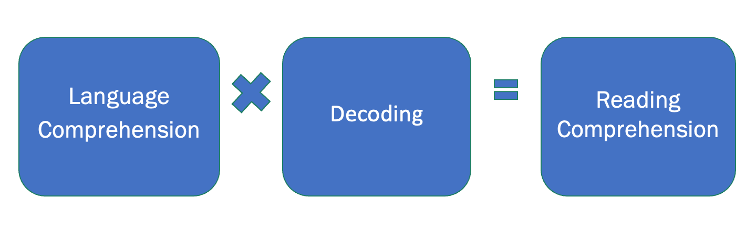

If we look at Gough & Tumner’s (1986) Simple View of Reading, there are two main skills students need to become competent readers: language comprehension and decoding skills (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Simple View of Reading (Gough & Tumner, 1986)

The visual is purposefully designed as a multiplication equation. If children lack decoding skills, but have a vast store of vocabulary knowledge, their reading comprehension will be compromised. The same is true if a child has strong decoding skills, but lacks adequate language skills—they too will struggle to be a competent reader. Both strong language skills and strong decoding skills are needed for students to read with comprehension.

Many of today’s Pre-K–3 literacy curricula emphasize children’s decoding skills such as letter sounds, rhyming, and phonics. Unfortunately, language development remains a neglected component in raising readers.

Here are two ways families can support their child’s literacy learning!

Book reading

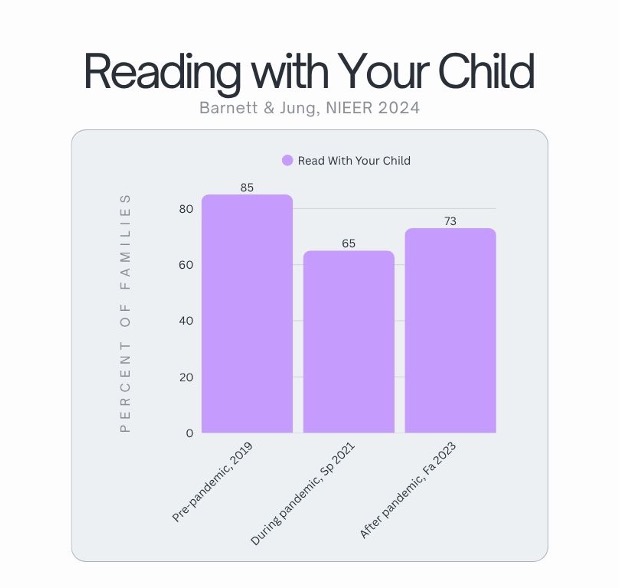

Research conducted by NIEER (2024) analyzed survey data collected 2019–2023. Over 1,000 parents responded to questions related to family activities they engaged in with their young children before the pandemic, during the pandemic, and again after the pandemic. Prior to the pandemic (2019), when asked if parents read to their child at home, 85% of families shared that they did read to their child at home. Not surprisingly, during the pandemic (spring 2021), that number fell to 65% of families sharing that they continued to read to their child. Most revealing: by fall 2023, after the impact of the pandemic, the percentage of families who read to their child at home had risen, to 73%—but had not yet returned to pre-pandemic numbers.

Research consistently demonstrates that reading aloud to children is a powerful way to build both vocabulary and background knowledge—key elements of language comprehension. Here are some examples of what families can do to support their child’s continued reading development:

- visit your local library

- let your child select books that are of interest to them

- make bedtime reading a moment to share in your child’s wonder of the new worlds and new words they find on the page!

If you’re looking for a research-based read aloud technique, look no further than David Dickenson’s dialogic reading (Dickinson & Tabors, 2001; Dickinson & Smith, 1994). Non-fiction texts exploring nature, animals, architecture, vehicles, sports, rainforests—any topic that’s of interest to the child—are a great place to begin. Highlight vocabulary specific to the topics that you can discuss with your child. Make connections to what they already know.

Dialogic reading will guide you to reread text, with each reading having a specific task. When I do read-alouds with young children, I like to begin with a picture walk to gauge their understanding of content we’ll soon read together. During a picture walk, we’ll informally identify images the illustrator has added to the book, or we’ll talk about a change in a character’s expression. Then we always dedicate first read-aloud as a listening-only experience. Rather than asking lots of questions and disrupting the flow of the book, we want to create a sacred space free of dialogue to appreciate the words the author has selected for their book. The next day, we may reread the same book, but now I may ask anticipatory questions: “What did the girl forget to buy when she was at the store?” or “Do you remember what will happen next?” Reading now becomes interactive as the child responds by recalling content from yesterday’s reading. By the third or fourth reading, I may read most of the text on a page, but then stop for the child to complete the remaining words of a sentence. Finally, after several readings the child may be able to retell the story on their own. We may act out the story together, or the child may draw their favorite part of the story and then dictate or write their recollection of the text. Children love to reread stories; we can make each reading an opportunity to instill a love and appreciation of words.

Conversations

Research from Harvard University’s Center for the Developing Child points to the power of serve-and-return in building children’s language development. There is no age limit on this activity. Even the youngest child can engage in this back-and-forth exchange with an adult.

First, we begin with what’s of interest to the child. As an example, you may notice they’re watching a bird outside the window.

Parent: “I noticed you were watching the cardinal outside the window this morning. Did you notice the color of the bird?”

Child: “It was a red bird and it flew from this tree down to the grass!”

Parent: “Yes, I think there’s a nest in the tree. I wonder if the cardinal has baby birds?”

Child: “Maybe that’s the mommy cardinal and she was looking for food for the babies?”

Parent: “You might be right! We have a book that has pictures of different backyard birds. Let’s see if there’s a picture of what baby cardinals look like.”

Child: “Then we can go outside—maybe we can see the cardinal feed her babies.”

This simple exchange went beyond simple yes or no responses. Instead the adult began with what was of interest to the child, and then expanded on their responses and offered correct terminology (nest, cardinal).

These same serve-and-return habits can be extended in daily home activities such as meal times. Harvard scholar Catherine Snow (2006) spoke often about the importance of conversation at the dinner table as a strategy to build children’s language development. Discussions about current events, or planning for an upcoming visit to the zoo, can help children organize and express their thoughts while also raising awareness of new vocabulary. Even simple shopping trips to the grocery store can increase word knowledge when we name our selections: kumquat, tangerine, pearl onions. Vocabulary is everywhere. We just have to use our words purposefully with children.

One final, no-cost learning opportunity is a strategy called Visible Thinking Strategies (VTS). It’s a way to help children build expressive language skills by talking about what they observe. The strategy is often used in museums but can be applied in many settings. Children are asked to take some time and really look at an image. Then they are asked three simple questions:

- What’s going on in this picture?

- What do you see that makes you say that?

- What more do you see/can you find?

You can practice this strategy by looking at the New York Times’s version of VTS, called “What’s Going on in This Picture?” Each week an image is posted that engages students from around the world to respond to the three questions. I would advise parents to carefully curate images based on their child’s readiness and development. The following week, the original article with additional information about the image is shared for students to then compare with their initial reactions.

Strategies such as book reading and conversations require only that meaningful time to connect with children is prioritized. If we follow their lead and build intentional opportunities for language development based on topics that are of interest to them, learning will at a minimum be sustained this summer—and perhaps even blossom!

References

NIEER (2024). Barnett, S. & Jung, K. Preschool learning activities: Fall 2023 findings from a national survey. https://nieer.org/sites/default/files/PLA_COHORT6.pdf

Center for the Developing Child (2024). Serve and return. Harvard University. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/key-concept/serve-and-return/

New York Times (2025). How to teach with What’s Going on in This Picture? https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/27/learning/how-to-teach-with-whats-going-on-in-this-picture.html

Snow, C. E., & Beals, D. E. (2006). Mealtime talk that supports literacy development. In R. W. Larson, A. R. Wiley, & K. R. Branscomb (Eds.), Family mealtime as a context of development and socialization (pp. 51–66). Jossey-Bass/Wiley.