Professors: Request an Exam Copy

Print copies available for US orders only. For orders outside the US, see our international distributors.

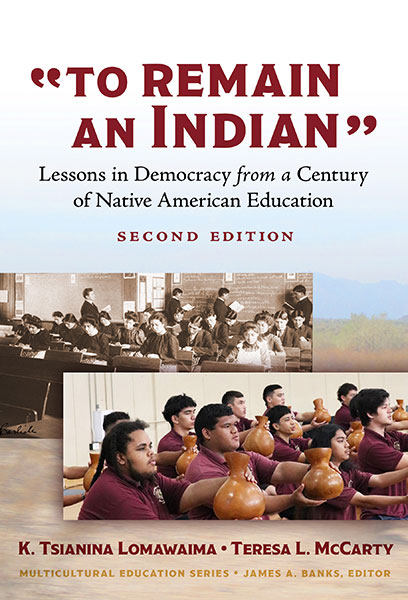

Second Edition

K. Tsianina Lomawaima, Teresa L. McCarty

Publication Date: December 24, 2024

Pages: 288

Series: Multicultural Education Series

“Offers a balm against despair (and) provides an inspiring theoretical frame for those who continue to fight for indigenous control.” —Tribal College Journal (of first edition)

"This second edition is essential reading for reckoning with the ongoing attempts to diminish Indigenous nations’ languages and cultures through schooling.” —Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻōpua, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

“To Remain an Indian” traces the footprints of Indigenous education in what is now the United States.

Native Peoples’ educational systems are rooted in ways of knowing and being that have endured for millennia, despite the imposition of colonial schooling. In this second edition, the authors amplify their theoretical framework of settler colonial safety zones by adding Indigenous sovereignty zones. Safety zones are designed to break Indigenous relationships and impose relations of domination while sovereignty zones foster Indigenous growth, nurture relationships, and support life.

This fascinating portrait of Native American education highlights the genealogy of relationships across Peoples, places, and education initiatives in the 20th and 21st centuries. New scholarship re-evaluates early 20th-century “reforms” as less an endorsement of Indigenous self-determination and more a continuation of federal control. The text includes personal narratives from program architects and examines Indigenous language, culture, and education resurgence movements that reckon with the coloniality of U.S. schooling.

Book Features:

K. Tsianina Lomawaima (Muscogee/Creek Nation and German Mennonite descent) is a scholar of Indigenous studies and a retired professor. Teresa L. McCarty is Distinguished Professor and GF Kneller Chair in Education and Anthropology and faculty in American Indian Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“Offers a balm against despair (and) provides an inspiring theoretical frame for those who continue to fight for indigenous control.”

—Tribal College Journal (of first edition)

“In this must-read second edition, Lomawaima and McCarty elaborate how settler safety zones are fundamentally about usefulness and domestication while highlighting the generative possibilities of Indigenous sovereignty zones, which are based on self-determination and relational abundance. Through robust archival and ethnographic research across multiple generations and diverse contexts, readers come to understand both the persistent attempted dismembering of Peoples, lands, and waters, and the sustained relational survivance of Indigenous communities and Native nations.”

—Angelina E. Castagno, professor, Northern Arizona University

“’To Remain an Indian’ has been a foundational text for understanding the landscape of settler colonial control in which Indigenous educators and activists have long asserted their visions of education. This new edition updates this genealogy of activism to highlight the everyday and collective ways that Indigenous people continue to mobilize zones of sovereignty in education on Indigenous terms and promote the resurgence of Indigenous languages, lifeways, and ultimately, Indigenous futures."

—Leilani Sabzalian, associate professor of Indigenous studies in education, University of Oregon

"Lomawaima and McCarty explore the deep ties between colonial education and land theft in America’s past, while bringing us close to Native educators, families, and leaders who continue to carve out zones of educational sovereignty. Essential reading for reckoning with the ongoing attempts to diminish Indigenous nations’ languages and cultures through schooling, more than a century on."

—Noelani Goodyear-Kaʻōpua, professor of Indigenous politics, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

Contents

Series Foreword James A. Banks xi

Acknowledgments xvii

Preface to the Second Edition xxiii

Indigenous Sovereignty: Lessons for Democracy and Much More xxiv

Indigenous Nations and the United States xxv

Lessons for Democracy xxvii

Goals for the Second Edition xxviii

What Does “To Remain an Indian” Mean? xxx

Where Do We Stand? xxxi

Overview of the Book xxxiv

1. Illuminating Safety Zones and Sovereignty Zones in a History of Native American Education 1

Schools as “Civilizing” and Homogenizing Institutions 5

Safety Zone Theory: Explaining Policy and Its Development Over Time 8

Methodological and Theoretical Approaches 13

2. The Strengths of Indigenous Education: Overturning Myths About Native Learners 19

Indigenous Education Versus U.S. Schooling 19

How and Why Do Stereotypes Endure? 20

Native Voices Teach Lessons of Shared Humanity 24

Indigenous Knowledge Guides Human Societies 25

Carefully Designed Educational Systems 29

Language-Rich Contexts for Education 32

Learning by Doing 38

A Return to Choice and Local Control 41

3. Women’s Arts and Children’s Songs: Domesticating Indigeneity, 1900–1928 44

Indians as Children: “Insensible Wards” 46

Boarding Schools Versus Day Schools 49

A Political Economy of School Practices: The “Dignity of Labor” 50

Race and the Safety Zone: Designating the Right Place 53

Attempts to Domesticate Indigeneity 60

An Unprecedented Possibility: “To Remain an Indian” 65

Conclusion 68

4. Power Struggles Over How “To Remain an Indian,” 1924–1940 69

Indian Citizenship Act of June 2, 1924 71

Piper v. Big Pine: An Early Ruling on School Desegregation 73

The “New” Vocational Education 75

Native Teachers in the Federal Schools 82

The Revival of Arts and Crafts Instruction 86

The Keystone of Control: Reforms Versus Business as Usual 90

Conclusion 95

5. Control of Culture: Federally Produced Curricular and Bilingual Materials, 1930–1954 96

“Indian History and Lore” Courses 96

The Bureau’s Indian Life Readers Series 100

The Pueblo Life Readers 105

The Sioux Life Readers 107

The Navajo Life Readers 111

The Hopi Life Readers 112

Native Translators and Interpreters 115

New Developments: Publication of Authentically Diné Stories 120

6. Carving Out Zones of Sovereignty: Bilingual-Bicultural Education and “Who Should Control the Schools” 123

Contours of the Safety Zone, 1950–1960 124

The Seeds of Transformation 126

Rough Rock—A School “The People Made for Themselves” 129

Rock Point Community School—Making the Most of a “Window of Opportunity” 135

The Peach Springs Hualapai Bilingual-Bicultural Program—“A School of Choice” 139

The Hard Labor of Sovereignty Zone Construction 143

7. “For the Benefit of My People”: Mobilizing Sovereignty Zones in Indigenous Language Reclamation 146

Mohawk Language Resurgence: “Our People Have Latched Onto the Idea of Becoming Speakers of Their Own Language” 149

Hawaiian Language Resurgence: “We Knew It Was Urgent and We Had People Willing to Take the Risk” 155

Diné Language Resurgence: “Giving Students Access to the Goodness of Being and Speaking Navajo” 163

Myaamia Language Resurgence: “We Must be Conscious Gardeners If We are Going to Have a Community Harvest” 168

A Genealogy of Sovereignty Zone Builders 173

8. Landscapes of Sovereignty Zone Opportunity 178

Landscapes of Opportunity in K–12 Schools 180

Landscapes of Opportunity in Postsecondary Education 189

Lessons in Democracy 197

Notes 201

References 207

Index 233

About the Authors 250

Professors: Request an Exam Copy

Print copies available for US orders only. For orders outside the US, see our international distributors.